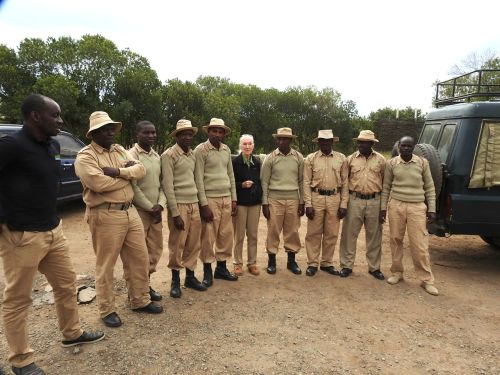

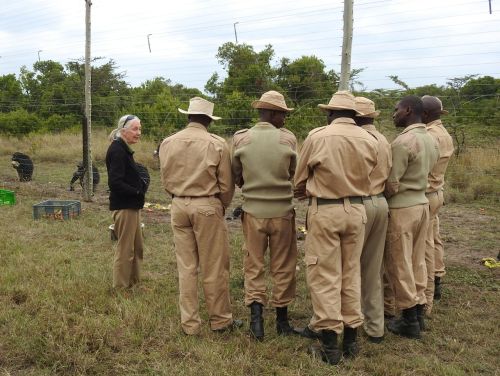

This is an edited, fascinating report prepared by Dr. Stephen Ngulu, Head – Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary/Ol Pejeta Conservancy Wildlife Veterinarian, recounting how Manno was integrated with the New Group. Chimpanzees are very territorial in the wild and each troop, or community, defends its home range against other chimpanzees to the death. A community does not easily accept a new unknown member, and in the wild strangers are more likely to be chased off or killed. The two communities of chimpanzees at Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary (SCS) were formed artificially from rescued individuals or small groups, but today they simulate closely troops in the wild.

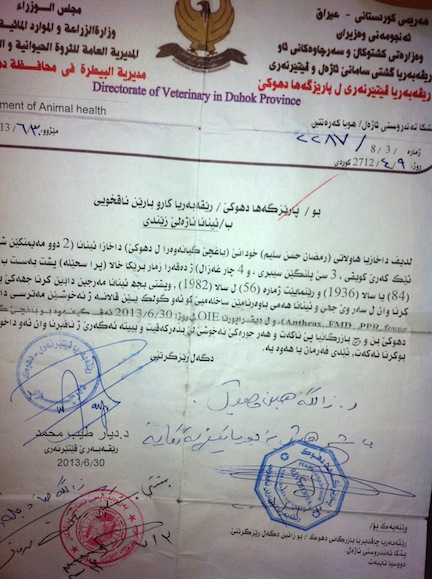

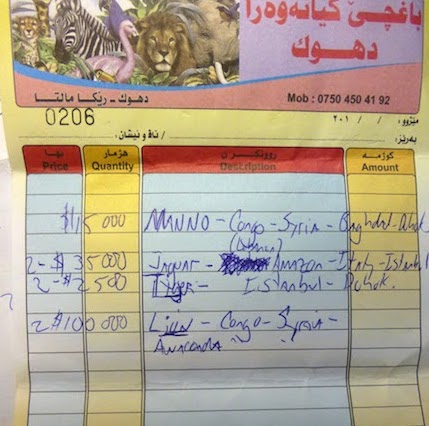

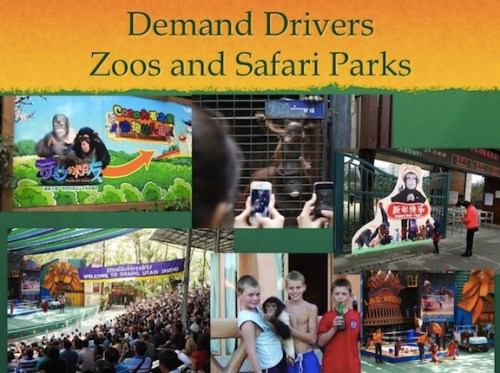

Manno is a four-year old male chimpanzee rescued from a private zoo in Iraqi Kurdistan. He lived there alone for about three years with no companionship except for humans, therefore he learned nothing about chimpanzee social behaviour. When Manno arrived at SCS the night of 30th November, 2016, staff knew from previous experience that it was going to be difficult to introduce him to the New Group, especially as there was a transition of alpha males going on, where two adult males were fighting one another for dominance and leadership of the community.

Manno was moved from the quarantine facility on 31st March and was put into the new chimpanzee house to begin integration. The first few days were a nightmare as he was nervous, restless and terrified. His fear subsided over the months that followed. He was gradually introduced to foster mothers. Progress was initially slow but we witnessed amazing success after we switched foster mothers [Akela to Jane]. Manno has since been completely accepted by all 14 chimpanzees in this particular group. Below is a brief week by week account of the integration process. [Some uneventful weeks have been omitted – Ed.]

31st March-6th April, 2016

Manno was transferred from the quarantine and kept separately. Akela was brought into a cage diagonally adjacent to Manno`s. He was observed to be curious albeit afraid to get close to touching distance of the separating half wall and grills. Lots of interest from Akela. No aggressive behaviour from this female was observed.

7th-13th April

Akela was moved to a cage immediately adjacent to Manno’s, interest was shown from both parties. Eye contact was established through the window grills but no physical contact.

14th-20th April.

Manno was moved to the main sleeping cages where the partition between the two was complete grill. Immense interest expressed by the foster mother Akela. Manno observed to be fearful.

21st- 27th April

Akela and Manno were put into same room. Akela made countless attempts to initiate friendship with Manno, spreading out both her arms and legs being a gesture to invite him to come closer, but Manno ignored her and would always run away whenever she tried to approach.

28th April-4th May

Akela continued trying all possible ways to attract Manno but no contact was observed. However, during feeding Manno would get closer to her with the gap between them being less than a meter.

5th-11th May

Akela succeeded to groom Manno’s foot briefly as he was feeding but he pulled away when he realized she was doing it.

12th-18th May

Akela was separated from Manno and Jane was brought in the adjacent cage, Manno avoided her, keeping a safe distance from the partition grill. Manno was put through an electric fence awareness training. This was done by fitting a mesh in the exit tunnel with a voltage of 4.2 kv. After close to ten minutes he came through the door and accidently touched the mesh getting a mild shock, he went back in the room for 5 minutes, came back through the tunnel but this time avoided touching any wires. [A grilled passageway connects the sleeping quarters with an outdoor fenced area. The fence is electrified to discourage escape. – ed.]

Jane was on the opposite side of the mesh and was clapping and doing some raspberries sounds to attract Manno`s attention but he avoided her, although at times he came closer but didn’t allow any contact at all.

On the 17th, both were put in the same room with an access to the tunnel, Jane positioned herself on the doors touching Manno anytime he came through the door, after close to four hours Manno got closer to Jane and remained when she touched him. Jane hugged him and engaged in active play/grooming for one straight hour; Manno observed to be extremely happy during this interaction.

19th-25th May Jane slept in the same cage with Manno for the first time. Bahati was moved in the adjacent cage to Manno, after a couple of minutes she groomed him as he sat close to the bars separating them. Jane was separated from Manno since she exhibited jealous behaviour when Bahati was interacting with him; this was meant to avoid the two fighting over him leading to a redirected aggression towards him from either of the females.

Bahati was introduced to Manno and immediately they engaged in active play for two hours taking breaks in between to groom him, after two hours together Jane was allowed to join but did not show any signs of aggression towards Bahati or Manno.

26th-30th May- Both females (Bahati&Jane) continued taking turns to play and groom Manno. He always ran to Jane for comfort when other chimpanzees were displaying and would be cuddled and groomed. The second electric fence training for Manno began this time in the tunnel that lead to the small enclosure, this was also meant to prepare him to be out in the small enclosure as well as seeing other chimps more with just an electric fence between them.

Akela joined them; she continued her efforts to befriend Manno and finally managed to touch and groom him briefly, this being a big step for Manno to trust her at last. The three females continued to interact with Manno. The next course of action was to allow the four Chimpanzees to have access to the exit tunnels that lead to the small enclosure.

7th- 13th June Manno, Akela, Bahati and Jane remained in the tunnel while the access to the small enclosure was prevented by an improvised electrified mesh, which he (Manno) didn’t touch.

14th – 20th June Manno was for the first time allowed to access the small enclosure after the electrified mesh was removed. For the first day he completely refused to join the females into the enclosure, until Jane carried him on her back. They engaged in active play chasing each other around bushes. Tess was put in a cage adjacent to Manno’s, she tried to touch him through the bars but he avoided her.

21st – 27th June Tess (female) was introduced to Manno and in the beginning he avoided getting close. Whenever Tess made a move to approach him he ran away, but with time he gained courage and got closer to her, but no contact was observed.

28th – 3rd July Physical contact was established between Tess and Manno. She carried and groomed Manno a lot. Joy (female) was put in a cage adjacent to Manno’s and she tried to initiate play with him, but to no avail.

4th – 10th July Joy was introduced to Manno’s cage, she showed no signs of aggression, and after a couple of minutes she approached him touching him gently. They hugged and kissed each other. They sat on the sleeping platform where she groomed him for some decent time.

18th – 31st July A lot of interaction was observed between Manno and the females (Tess, Joy, Jane, Bahati and Akela) all taking turns to play with him.

1st – 7th Aug Chipie (female) was put into a cage adjacent to Manno’s, he was displaying aggressively towards her due to her small size, but she was so friendly putting her arms through the bars to touch him and was introduced to him on the fourth day when they both hugged each other with, Chipie grooming and carrying him a lot.

8th – 21st Aug Dufa (female) was put in a cage close to Manno, he displayed towards her, but she was very calm putting her arm through the bars patting his back gently, both played through the bars. Dufa was put in same room as Manno, they both engaged in active play immediately but Bahati was very protective pulling Manno away from Dufa.

21st Aug – 3rd Sep Amisero (female) was put in a cage next to Manno, she showed no interest in him in the beginning. She was physically introduced to him on the seventh day in his cage. Manno kept a distance and avoided her every time she approached. After some time Manno gained courage and approached Amisero, who tickled, groomed and carried him around the small enclosure.

4th – 10th Sept Niyonkuru (recently dethroned Alpha male) was put in a cage next to Manno, he was a bit aggressive towards the females but was calm after some time. He put his arms through the bars to touch Manno but Dufa went in between and tried biting Niyonkuru in what looked like protecting Manno from Niyonkuru’s unpredictable aggression.

5th – 11th Sept Niyonkuru was reintroduced to all the females before physically introducing him to Manno. This was done to calm him down after a spell of separation. He was a bit aggressive towards some, but after time he calmed down.

12th – 18th Sept Niyonkuru was introduced to Manno while he was in the company of all the females. This took place with the exit to the small enclosure opened to enable Manno to have an escape route in case he was attacked. Food was scattered in the small enclosure to distract Niyonkuru. Manno at first avoided him, but as Niyonkuru was foraging he approached Manno while stamping the ground with his foot and chased him in a playful way, but he (Manno) ran away.

25th Sep – 1st Oct Niyonkuru was playing a lot with Manno and was seen carrying him a few times. Roy (male) was put in a cage adjacent to Manno; he (Roy) started tickling him through the bars. We Introduced Roy to Manno while he was in the company of all the females, they immediately engaged into an active play that lasted close to ten minutes.

2nd – 8th Oct Romeo (male) was put in a cage close to Manno’s. Romeo was afraid of the females and avoided getting nearer, but was introduced to Manno while in the company of Akela, Jane and Bahati. Manno and Romeo immediately started chasing each other around the cage. Uruhara (male) was put in a cage next to Manno, and although he put his arms through the bars in attempt to touch and groom, Manno stayed away.

9th – 14th Oct We introduced Uruhara to Manno in the cage, but the door to the small enclosure was left open. Manno was in the company of all the other chimps except Kisa and William, the last two who had not yet met Manno. Manno stayed away from Uruhara, but a few minutes later he (Manno) approached Uruhara and started to play with his legs. They both went out in the tunnel where they played continuously for ten minutes.

William (the new alpha male) was put in a cage next to Manno. During this period Manno was for the first time released in the big enclosure with all the other chimps, except Kisa and William. He was very excited, all the females followed him all the way carrying him when he was exhausted.

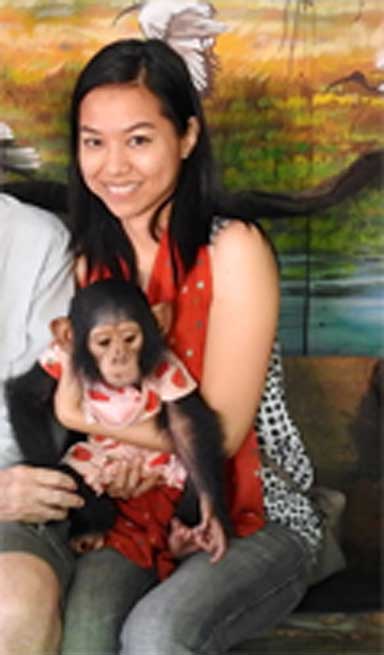

Manno was finally released into the big enclosure (Manno circled in red) where he could interact with the whole community.

15th – 21st Oct William (alpha male) was introduced to Manno while he was together with all the other chimps, except Kisa. All was calm and Manno was in the tunnel being groomed by Joy, when William tried walking towards Manno. Joy called an alert and all the females ganged up and attacked the alpha (William). [This is why the females were introduced first to Manno, in the hope that they would form a protection sisterhood from aggressive males. It worked. – Ed.] William was later seen to interact positively with Manno.

Kisa was put in a cage next to Manno, he initiated a play with him through the bars, and in the beginning Manno stayed away only to join him later where they tickled a lot. Kisa was finally physically introduced to Manno in the house with the door leading to the small enclosure wide open; this was meant to give room for Manno to escape when necessary. They started playing, immediately chasing each other through the tunnel and resting for a grooming session.

Conclusion

Manno’s Integration can be described as a process that was devoid of negative drama, aggression and rejection. This kind of positive integration can be largely attributed to Manno’s tender age and the valuable experience of the sanctuary staff in terms of their understanding of resident chimpanzee behaviour, group dynamics and social structure.

We expect that as Manno continues to grow and bond with his new family, he will sooner or later be exposed to group confrontations and dominance fights between the other males. Such scenes will obviously be a new thing to him and he may choose to get involved without suitable prudence. It is in such circumstances that he may occasionally get injured/bitten, but this is expected in any chimpanzee troop.