Editor’s note: This article is reprinted from Mongabay.com

13 Feb 2026

- Türkiye has refused to return a western lowland gorilla named Zeytin, who was smuggled out of Africa a year ago; Turkish authorities seized him as an infant from the cargo hold of an airplane headed to Bangkok.

- The decision marks an about-turn in Türkiye’s plans to return him to Africa, where he’d be in a Nigerian sanctuary with other gorillas, after a DNA test ruled out Nigeria as his country of origin. Turkish authorities announced he will remain in the country permanently.

- Gorillas are social animals that live in family groups, and with no other gorillas in the country, conservationists worry Zeytin will be doomed to a life of isolation in a zoo.

- Conservationists urge Turkish officials to reconsider their decision and send the baby gorilla to a sanctuary in Africa as soon as possible so he has a better chance of possible release into the wild.

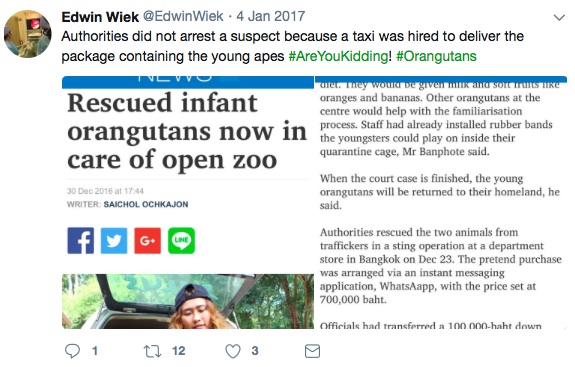

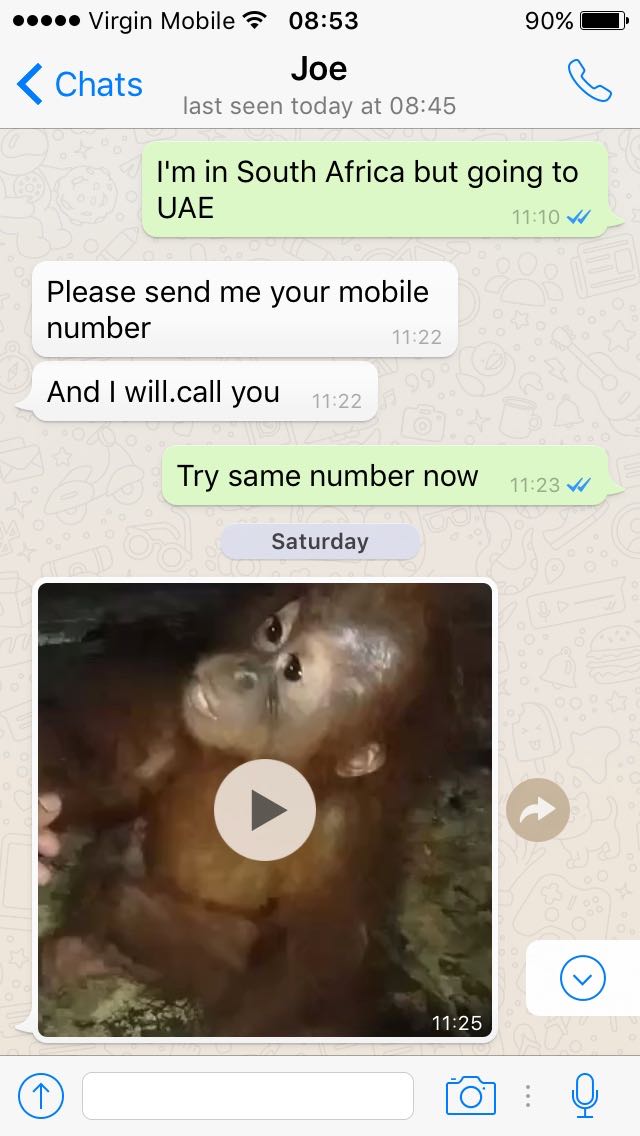

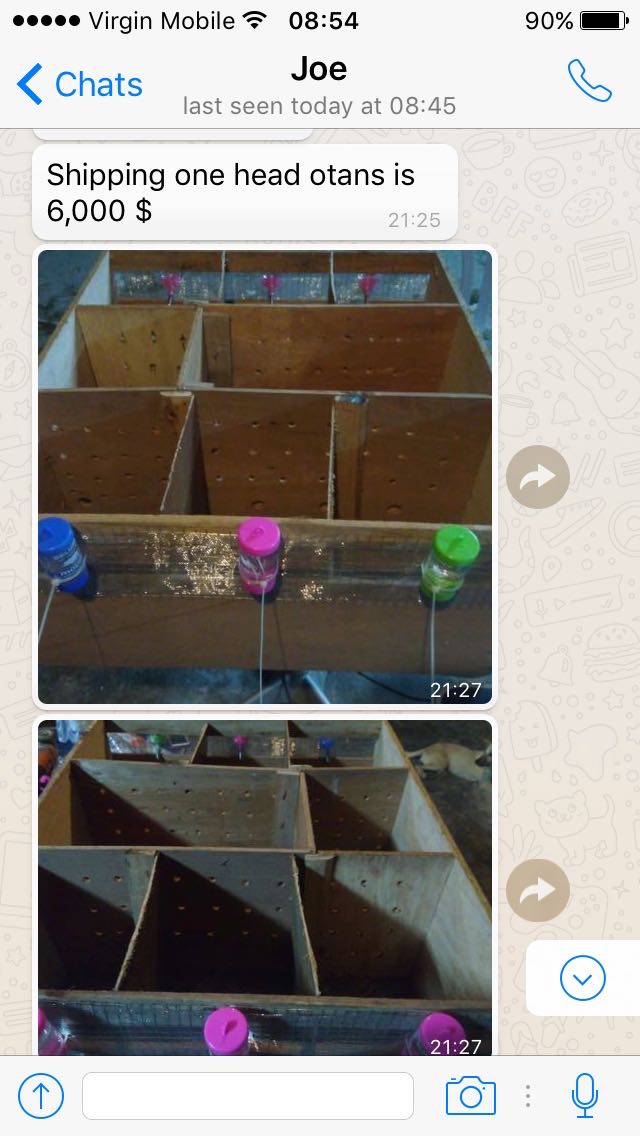

In December 2024, Turkish customs officers were flummoxed when they discovered a malnourished baby gorilla in the cargo hold of an airplane flying from Nigeria to Bangkok, transiting via Istanbul. Wearing a soiled T-shirt, the 5-month-old infant was shoved inside a wooden crate falsely declared to contain 50 rabbits. After a social media campaign, he was named Zeytin, which means “olive” in Turkish.

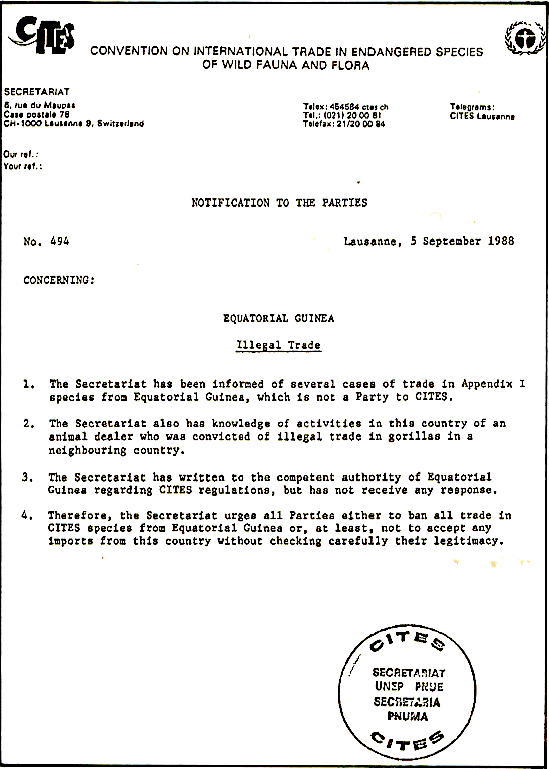

This critically endangered western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) was being smuggled to an animal farm in Bangkok without any export permits or paperwork. All great apes, including gorillas, are afforded the highest protection under CITES, an international treaty regulating wildlife trade, making commercial transnational trade illegal. They can be transferred between zoos or exported for scientific research but require official paperwork.

After the seizure made global headlines, Turkish authorities sent Zeytin to Polonezköy Zoo in Istanbul. Meanwhile, they said they were working to imminently dispatch him to a sanctuary in Africa, where he could possibly be released into the wild.

But one year on, those plans seem to have bitten the dust. As of September 2025, Zeytin was seen languishing in the same zoo, living a lonely life in a cage — the very life many thought he had escaped.

“At present, Türkiye does not have adequate facilities to meet the long-term physical, social and psychological needs of a gorilla,” said primate expert Aslıhan Niksarlı at the Jane Goodall Institute who directs Roots & Shoots Türkiye. “There are also no other gorillas in the country, which means that Zeytin continues to live in isolation.” Niksarlı has worked with the Turkish authorities since the seizure, supporting his care.

Gorillas, like humans, are social beings. They need the company of their own kind to thrive. In the wild, they live in hierarchical family groups and develop complex bonds with each other, said Jacqueline L. Sunderland-Groves, a member of an IUCN group focused on great apes.

“Zeytin’s current situation provides no opportunity to live with other western lowland gorillas,” she said. “It is never recommended to keep a gorilla alone in captivity.”

Only a tiny fraction of seized wildlife ever returns to the wild. “Reintroduction is a notoriously difficult process that takes years of careful planning, at least 5 to 10 years, and significant financial commitment,” Iris Ho, head of campaigns and policy at the U.S.-based nonprofit Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA), said in an email. “Shrinking wild habitats due to human activities make it extra challenging to find suitable locations for successful reintroduction.”

But the decision to keep Zeytin locked up in a zoo will rule out reintroduction altogether. Captured as an infant, Zeytin has already missed out on the constant care he’d have received from his mother and the essential social and survival skills he’d have learned from her and other family members as a young gorilla. Without these skills, life in the wild would be impossible. He’d be forced to remain in a zoo.

“A zoo is a completely different environment to a gorilla’s natural environment, and one where Zeytin is being exposed to human pathogens, whilst at the same time gradually losing his ability to tolerate pathogens present in his natural habitat,” Sunderland-Groves said. “If he remains in Türkiye, there will be no opportunity for integration with other young gorillas or for possible reintroduction.”

A DNA test that reversed Zeytin’s future

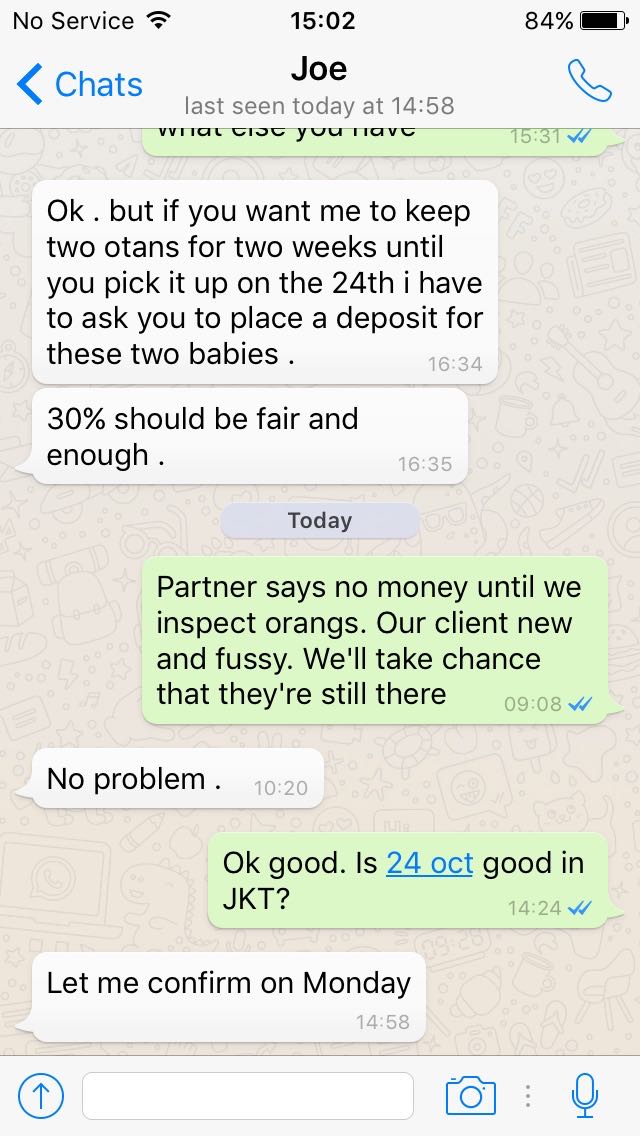

Turkish authorities confirmed in August 2025 that they were working to send Zeytin to the Drill Ranch, a primate sanctuary in Nigeria. That sanctuary hosts primates, including great apes such as gorillas and chimpanzees and is accredited by PASA, which has a network of primate sanctuaries in Africa.

Kadir Çokçetin, general director of Türkiye’s Nature Conservation and National Parks department responsible for Zeytin’s custody and care, told local media in August that talks were in the “final phase” for his rehabilitation. Turkish Airlines would be flying him home, he said, adding, “We hope to send Zeytin back to Nigeria very soon.”

But a month later, Turkish authorities announced they’d nixed the plan, and Zeytin will remain in the country permanently. That decision followed DNA tests, which revealed he was not native to Nigeria. Officials told local media they couldn’t repatriate him under international wildlife trade rules and would rather have him live his life as a zoo attraction.

Sunderland-Groves from IUCN’s great apes group says, “Ideally, trafficked apes should be returned to the country of origin if there is suitable care available there.”

CITES recommends returning confiscated live animals to the country of export. “When the country of origin is unknown or there is no suitable sanctuary available in-country, the priority is for the animal to receive care by a reputable sanctuary located within the species or subspecies’ geographic range,” Sunderland-Groves said. Such sanctuaries not only have trained staff who can care for complex species such as gorillas but also have other individuals of the same species for socialization.

In Zeytin’s case, authorities know he was exported from Nigeria, but no one knows exactly where he came from because his traffickers weren’t arrested. Western lowland gorillas inhabit the forests of West and Central Africa, all the way from Cameroon to Angola and the Congo Basin.

At Nigeria’s Drill Ranch, Zeytin would be in the company of another young western lowland gorilla.

“Zeytin could be housed with [the juvenile] until both gorillas could be transferred to a range country sanctuary,” Sunderland-Groves said. She added that a specialized sanctuary in the Republic of Congo, which is within the western lowland gorilla’s native range, could be an ideal home for both. “They could be integrated with similar aged gorillas confiscated from illegal trade and rehabilitated for possible release into the wild.”

Conservationists urge Türkiye to send Zeytin home

Since their October decision to keep the baby gorilla, Turkish authorities have remained mum about his whereabouts and well-being, conservationists say. “I am keen to learn from the Turkish government [about] the welfare status of Zeytin since we have not seen any social media posts or other updates by the government,” PASA’s Ho said. “We also have no information about which zoo will house Zeytin following the government’s announcement last October.”

At the November meeting of CITES delegates in Uzbekistan, Zeytin’s case was mentioned during a discussion about the Great Apes Enforcement Task Force, an international network to strengthen law enforcement for gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and orangutans that are trafficked worldwide. Speaking there on behalf of several conservation organizations, Ho urged Türkiye to reconsider its decision to keep Zeytin in “solitary captivity indefinitely” and repatriate him to Africa so he has “a chance at reintroduction in the wild.” But there has been no commitment to do so, she said.

Mongabay reached out to CITES authorities in Türkiye and Nigeria to seek an update on Zeytin’s repatriation but did not receive a response before publication.

“Türkiye has a track record of responsible and commendable repatriation of confiscated animals to Africa,” Ho said, referring to the country’s decision to return 112 confiscated African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus) to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2024. “I hope that Türkiye will reconsider its decision and repatriate Zeytin to Africa, where he belongs.”

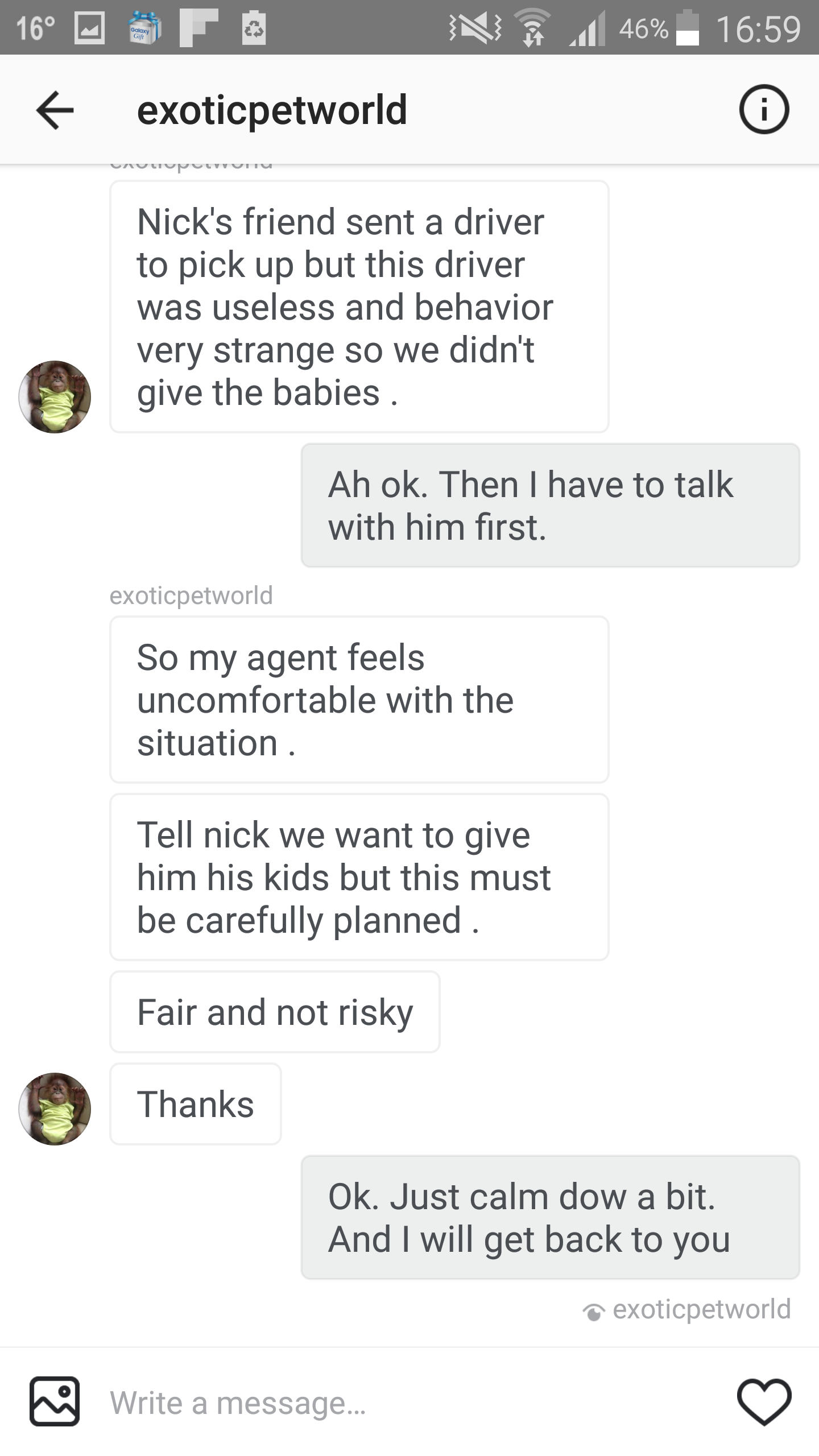

Fueled by increasing demand for exotic pets, gorillas and chimpanzees continue to be smuggled to countries across the world, used in tourist attractions and trafficked to meet increasing demand for exotic pets, according to a recent PASA report. Some of the legally traded individuals have questionable origins, it said. How Zeytin’s case is handled could show the world’s commitment — or lack of it — to the future of our closely related cousins.

“With every great ape species at risk of extinction, each individual is a priority for conservation,” Sunderland-Groves said. “Prosecuting the individuals responsible for this criminal activity, together with returning Zeytin to a country within his subspecies range, sends a strong message that great ape trafficking will not be tolerated, and that countries are willing to cooperate to address the poaching and illegal trade that threatens our closest relatives.”

Ho said her organization stands ready to provide support to the Turkish government, should authorities choose to reconsider their decision and return the gorilla to his native Africa. “Our goal is to ensure Zeytin’s best long-term well-being and to give him an opportunity to live among his peers, with eventual reintroduction in his natural wild habitat when appropriate and feasible.”

Banner image: A photo of Zeytin posted by the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry on Facebook in December 2024. No further updates have been provided since the country announced it will not send Zeytin back to Africa. Image courtesy of Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry via Facebook.

VIEW THE COMMENTS