Ed. note: Africa Geographic first published this article https://africageographic.com/stories/how-drcs-endangered-chimpanzees-end-up-in-a-billionaires-indian-zoo/.

Posted on April 10, 2025 by Daniel Stiles

An operation involving the transfer of endangered chimpanzees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to India has sparked international outrage and serious questions about wildlife trafficking, corruption, and misuse of CITES permits. At the centre of the controversy is a high-profile Indian zoo project, Vantara, and DRC wildlife authorities accused of misrepresenting wild-caught animals as captive-bred to facilitate their export. Conservationists warn that this case could signal a dangerous new chapter in the global illegal wildlife trade.

The trafficking of chimpanzees from the DRC has long been a troubling issue. The country is home to vital populations of great apes, but widespread poaching – often for the bushmeat trade – frequently results in orphaned young chimpanzees being captured and sold. Sanctuaries like Lwiro Primate Rehabilitation Centre serve as a refuge for these animals, working to provide care and eventual rehabilitation. However, these efforts are threatened by corrupt practices, as highlighted by the recent attempt by DRC’s Congolese Institute for the Conservation of Nature (ICCN), the wildlife authority of the DRC, to remove chimpanzees from Lwiro, allegedly under the guise of a zoo revitalisation project.

In early January this year, the staff at Lwiro in the eastern DRC were surprised when a delegation led by the head of the Kinshasa Zoo arrived unannounced with a letter authorising them to pick up 12 chimpanzees.

The letter was signed by Yves Milan Ngangay, Director General of ICCN, which is also responsible for the nation’s sanctuaries and public zoos.

The Lwiro sanctuary, situated in a tropical forest 45km from Bukavu, just outside Kahuzi-Biega National Park, is home to about 130 chimpanzee survivors of poaching and attempted trafficking. Many saw their mothers butchered for bushmeat before their eyes and are undergoing rehabilitation at Lwiro.

The staff courageously refused to hand over the chimpanzees, and ICCN left empty-handed. Local community and conservation groups heard about the incident and issued a strong press release on 12 January condemning the attempt to “capture 12 chimpanzees at the Lwiro Primate Rehabilitation Centre. This action, initiated by the ICCN general management, constitutes a serious threat to the conservation of these endangered primates and undermines the commitment of many international partners.”

Two days later, Ngangay released an official communique.

The communique announced a five-year programme to renovate the country’s zoos and botanical gardens to strengthen their role in biodiversity conservation by collecting various primate and artiodactyl (even-toed ungulate) species for research, staff training and conservation breeding.

In the communique, he criticised those who had stopped the lawful transfer of the primates to begin the “experimental” work at the Kinshasa Zoo.

Most noteworthy in the communique was that “the collection of specimens by the Institute in this vast programme can only be made from sanctuaries or else from rehabilitation centres and public and private animal parks, depending on their status and relationship with the Institute”

Several critics of the scheme have pointed out that the dilapidated Kinshasa Zoo does not have the facilities, staff or financial capacity to implement the programme presented by ICCN.

“If the mission is true, the chimpanzees will be sent to a real death trap,” warned Sara Rosenberg, a former volunteer at the Lwiro Primate Rehabilitation Center, referring to the transfer.

AG has received screenshots from videos taken on 25 January 2025 showing the zoo and chimpanzees in cages there. In the videos, the zoo indeed did appear to look in a deplorable state, with animals sitting in filthy, cramped, dilapidated cages with no items or structures offered for enrichment.

Chimpanzees turn up at Kinshasa Zoo – from where?

On 13 February this year, Ofir Drori, founder-director of the wildlife law enforcement NGO EAGLE, posted a press release on their website, seen by AG but since removed, stating that in recent months, nine chimpanzees had arrived at the Kinshasa and Kisangani zoos from unexplained sources. Drori speculated that the chimps had been collected with the intention of selling them and stated:

“Links from ICCN lead to a likely buyer of the chimps. There has been a major rise in primates and other wildlife shipping to India for the past 6 months, with a sole buyer: the so-called Greens Zoological Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre (GZRRC).” GZRRC is the original name of Vantara, which aims to be the biggest zoo in the world. It is owned by Mukesh Ambani as part of GZRCC and headed up by his son, Anant Ambani.

Later that day, on 13 February, the chimps were flown to India on a private jet. Our sources later confirmed that the chimpanzees had arrived at Vantara.

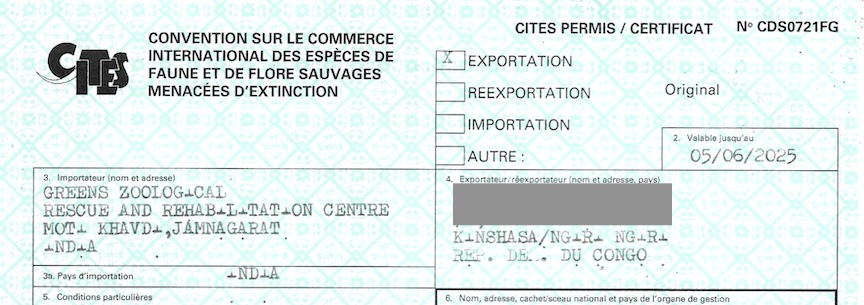

The DRC CITES export permit lists nine chimpanzees in the shipment, with a “Z” (zoo) purpose code and “C” (captive-bred) origin. To use a “C code”, the Appendix I specimens must have been second-generation born in captivity, and their progenitors must have been acquired legally.

Contacted by AG, Ofir Drori said, “There are no great ape breeding facilities anywhere in Africa, and the chimps at the Kinshasa Zoo were certainly not bred in captivity. The wild is the only logical source for them.”

The chimpanzees, therefore, were not acquired from lawful sources. This contradicts the specification made in the ICCN official communique that states collection “can only be made from sanctuaries or else from rehabilitation centres and public and private animal parks according to the laws applying to them”. The CITES permit states that the Kinshasa Zoo is the exporter. This fact also contradicts the stated purpose of collecting the chimpanzees in the first place, which was “for research, staff training and conservation breeding”.

“They were collected to sell,” said Drori.

ICCN has denied the selling of chimpanzees. In an interview with Mongabay Africa, chief site director of the Kinshasa Zoo, Matata Ngirabose Bruno, who also headed the ICCN mission that visited Lwiro, categorically said that “the zoo does not sell animals”.

It is also important to note that past instances of wildlife trafficking have involved permits allegedly falsified by the ICCN.

The probable source of the chimpanzees

ICCN documents dated 27 December 2024, seen by AG, authorise the collection of eight chimpanzees found in captivity in villages around Buta, which is in northeastern DRC about 200 kilometres north of Kisangani. They were to be transferred to the Kinshasa Zoo by 12 January 2025.

Therefore, these chimpanzees will have been present in Kinshasa Zoo when EAGLE reported the arrival of chimps from unknown sources. It also placed these chimps at Kinshasa Zoo just a month before nine chimpanzees were exported from the zoo to Vantara.

The young chimps found in captivity in villages were likely collateral damage to bushmeat hunting, and therefore, they were captured from the wild. Under normal circumstances, such recovered chimpanzees are sent to a sanctuary for rehabilitation and proper care – not to a zoo, with little capacity to offer care and rehabilitation to the young chimps.

This also brings into question the listing of the source of these chimps as “Code C” (born in captivity). The fraudulent listing of source codes as “Code C” is a well-known tactic in trafficking circles, known as a “C-scam”. Examples of the relatively common C-scam can be found in a recent report on great ape trafficking published by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime. CITES has dealt with such cases in the past by ordering a suspension of trade by the offending parties until remedial action is taken.

Not the first shipment to Vantara

On 6 March 2025, United for Wildlife released an alert alleging that “from March of 2024 at least eight consignments of CITES-listed primates, including chimpanzees, an Appendix I species, and other wildlife were shipped on flights from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to India.”

The alert stated: “The consignments possibly contained laundered and smuggled species hidden amongst legally traded animals, including chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas, and permits associated with the consignments may have been falsified, according to multiple confidential sources.”

DRC CITES export permits issued between 6 December 2024 and 30 January 2025 also indicate the importer as GZRRC.

Other allegations made against Vantara

In March of 2024, M Rajshekhar published an article on Vantara in the Himal Southasian newspaper. The article highlighted numerous irregularities in the origin of Vantara’s elephants from within India. It also pointed to further irregularities in the origin of other endangered species from international suppliers who were not the usual sources of animals in need of rescue and rehabilitation. The sources appeared to be commercial exotic animal traders or sources with records associated with illegal wildlife trade.

On 6 March this year, the Wild Animal Protection Forum of South Africa issued a report that questioned the extensive range of species (36) and high number of animals (765) exported to Vantara. It highlighted various problems with the different species exported, which Vantara asserts were all rescues from detrimental circumstances.

The WAPSFA report expressed concern about Vantara’s breeding plans: “The lions and tigers exported from South Africa appear to have been purchased and exported from breeding facilities in South Africa… They will now be transformed into breeding machines, exploited within the numerous animal breeding facilities (nurseries) outside the main zoo.”

The report continued: “WAPFSA would need to be convinced, based on independent, verifiable evidence that the additional list of species exported from South Africa were saved or rescued from adverse conditions.”

Later in March, the UK-based Independent reported that Vantara had dismissed the complaint by the South African coalition as “entirely false and baseless” and said they had served them a legal notice over the report.

On 13 March, the Süddeutsche Zeitung published an investigative article that alleged many irregularities regarding the sourcing of animals at Vantara, including the probability that some had been sourced from the wild, not captivity. The article alleged that 39,000 animals were being kept in Vantara by the end of 2024.

A European wildlife dealer is quoted in the article as stating, “Regardless of which wholesaler I talk to, the supply of wild animals is bought up. The supply lists are getting shorter because everything goes to India.” The fact that this demand also leads to more wild captures was “obvious” to the animal dealer.

Further action

ICCN is currently collecting other animals listed in Vantara’s “rescue list”, including bonobos and gorillas. A concerned group of wildlife NGOs has drafted a letter to the CITES Secretariat detailing several instances of trade irregularities involving Vantara, including the chimpanzee trade reported here, and entreating amongst other measures that the Secretariat and the Standing Committee (SC) request that:

- India agrees to suspend imports of live specimens of CITES-listed species until this issue can be discussed at the 79th meeting of the CITES Standing Committee (SC79);

- Parties refrain from issuing permits to export live animals of CITES-listed species to India until this issue can be considered at SC79.

The 79th meeting of the CITES Standing Committee will be held in November this year in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, immediately preceding the Conference of the Parties. The issue around Vantara is set to be one of the most contentious items on the agenda, pitting NGOs against a powerful billionaire family.

As international scrutiny intensifies, the case of the trafficked chimpanzees highlights the urgent need for stronger enforcement of wildlife trade laws and greater transparency in both exporting and importing countries. The upcoming CITES Standing Committee meeting in Uzbekistan could prove pivotal in setting new precedents for accountability, especially when powerful private interests are involved. For now, the fate of the trafficked chimpanzees – and potentially many more endangered species – rests on whether global conservation authorities are willing to confront systemic loopholes and hold perpetrators to account, regardless of their influence or wealth.