In late April PEGAS assisted Phoebe McKinney, founder of the NGO ISPARE, to rescue two young chimpanzees in Liberia from truly appalling conditions of illegal captivity (see Part I).

Jackson, renamed Guey, was living on an abandoned VW bus before rescue. (Photo: P. McKinney)

Jacksy, renamed Sweatpea, receives a back-scratch from the PEGAS manager in her bleak, filthy cage before rescue. (Photo: P. McKinney)

They were both rescued and relocated to a temporary enclosure at the Libassa Wildlife Sanctuary, located in a patch of coastal forest about 40 km from Monrovia.

Guey and Sweetpea meeting for the first time in their new enclosure at Libassa Wildlife Sanctuary, free to run and play with another chimpanzee for the first time in their lives. Mbama, their caretaker, looks on. (Photo: D. Stiles)

The Libassa sanctuary is not equipped to look after chimpanzees over the long term. As they grow into adulthood chimpanzee infants, who are friendly and unaggressive, become increasingly forceful and surprisingly strong. Rudolphe Antoune, owner of the Libassa Ecolodge and land on which the sanctuary is located, had witnessed a captive adult chimpanzee violently break out of a barred cage and knew that the wire mesh enclosure would not be adequate for very long. Even if a strong enough enclosure could be constructed to hold grown chimpanzees, the support was not there for long-term care, which needed a full-time manager, veterinarian and trained caretaking staff.

The only hope was to bring the chimpanzees to Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary in Kenya. No other sanctuary in Africa had the capacity to accept them. The United Nations Great Ape Survival Partnership (GRASP) was aware that there were many chimpanzees in Liberia in need, but they had been unable to find a solution.

Before leaving Liberia the PEGAS manager met with the Liberian head of the national CITES office and obtained his agreement that they would issue a CITES export permit for the chimpanzees, on the condition that Kenya would issue the corresponding import permit. Veterinary health clearances would also be necessary.

PEGAS also visited the Kenya Airways office in downtown Monrovia and spoke with the Cargo Officer about the requirements for transporting chimpanzees from Monrovia to Nairobi. Because of the Ebola crisis, Kenya Airways had suspended its scheduled Monrovia-Nairobi flight via Accra. We would have to wait for them to resume service, or use other airlines, which required changing planes and airlines in a third country, another complication.

As the complexity and difficulty of the task ahead became more apparent, PEGAS decided to visit the ‘Monkey Island’ chimpanzee colony, located near the Robertsfield international airport, just down the coast from Libassa. The misnamed Monkey Island contained over 60 chimpanzees abandoned by the New York Blood Center, and PEGAS was aware that plans were afoot to seek long-term care for them. Might those plans be able to embrace chimpanzees languishing in squalid, lonely circumstances around Monrovia? And might Guey and Sweetpea be the first to go?

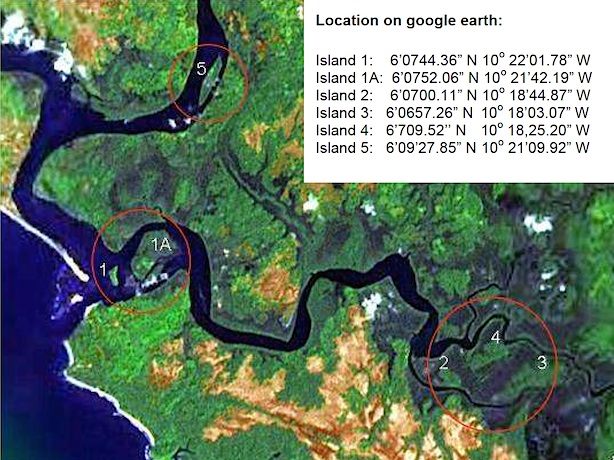

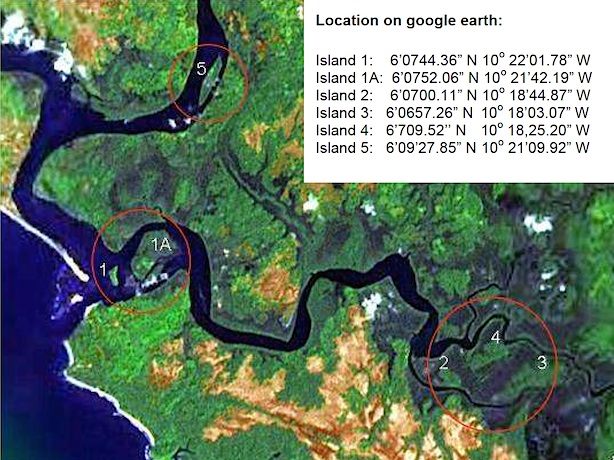

Map showing the location of Monrovia and the chimpanzee islands in the red oval.

The so-called Monkey Island actually consists of six islands in the Farmington and Little Bassa rivers, very near to the Atlantic Ocean. At the time of PEGAS’s visit there were 66 chimpanzees on the islands, but because of the lack of funds contraception had not been practiced for a few years and there were now more than ten infants under the age of 5 years to contend with, and more would surely be on the way if nothing was done. There was no wild food to speak of on the islands and caretakers had to bring food by boat, so allowing breeding was not a good idea.

Location of the LIBR chimpanzee islands. (Photo courtesy of D. Cox, Jane Goodall Institute)

The history of how the chimpanzees came to be on the islands is long and tragic. To summarize briefly, in 1974 the Lindsley F. Kimball Research Institute of the New York Blood Center established a Laboratory of Virology (VILAB II) in Liberia for research with chimpanzees. They took over a defunct Liberia Institute for Tropical Medicine, which the Liberian government renamed the Liberian Institute for Biomedical Research (LIBR). The New York Blood Center (NYBC) staffed and managed the LIBR in cooperation with the government from 1975 to 2002. Chimpanzees were caught in the wild and brought to VILAB II for biomedical research.

During the years of Liberian civil wars (1989-1996, 1999-2003), NYBC staff remained at the site and continued research activities and care for the chimpanzees, at considerable cost to themselves. This prevented the chimps from being slaughtered[1]. Research at the LIBR facilities in Liberia by NYBC led to a Hepatitis B vaccine and also contributed to the validation of a sterilization method that eliminated transmission of Hepatitis B and C and HIV viruses through blood products, so the chimpanzees deserve considerable gratitude for their sacrifices to science.

Since 1986, the research carried on in Liberia by the NYBC at LIBR using chimpanzees is reported to have contributed to the receipt by the NYBC of more than USD 500 million in royalties. Even with a stipulated provision in the agreement with LIBR that “LIBR will receive 5% of such royalty income as shall accrue to NYBC resulting in part or in whole from NYBC operation in Liberia”, LIBR was never informed about or received its share of the more than USD 500 million – about USD 25 million! The NYBC also signed agreements with the LIBR in 1999 and 2002, but after that time did not continue to use chimpanzees in research. The chimpanzees were gradually moved from the LIBR facility in Charlesville, about 7 km from the Robertsfield airport, onto the islands.

The NYBC had provided for the care of these animals in “retirement” on the islands, where they are safe from human predators, and local people are also safe from the animals, which having lost their fear of people can be dangerous. Because there is little wild food on the islands, the chimpanzees have to be fed by caretakers whom they have come to know and trust and provided with other care at a cost of about USD 30,000 per month. The NYBC on 5th January 2015 unilaterally announced that it would cease all support for the chimpanzees. Without concluding any formal discussion of the transition, NYBC ceased support for the care of the chimps on 6th March 2015. Since then, the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) and the Arcus Foundation have been providing funds to continue feeding the chimpanzees.

Joseph Thomas, with John Zeonyuway in the pick-up organizing food, two of the main staff in late April looking after the chimpanzees. (Photo: D. Stiles)

When PEGAS visited in late April 2015 the caretakers were taking food and milk to the chimpanzees, but because of a lack of funds the chimpanzees were being fed only every second day, which was barely keeping them alive. I joined a boat that had been arranged to take three visiting scientists from the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, the USA, who kindly allowed me to tag along.

John Zeonyuway on the left, setting off from the dock with three CDC scientists to visit the chimpanzee islands. (Photo: D. Stiles)

We travelled down the Farmington River for less than a half an hour until we reached Island 5. The chimps had heard the sound of the outboard motor and were eagerly awaiting their fruit, sugar cane and milk. John bounded out of the boat into shallow water and began distributing fruit from a basin. The chimps shrieked and hooted their happiness, and then dug into the food like famine refugees, which in a way they were.

The chimpanzees dig into the fruit basin with delight. (Photo: D. Stiles)

Each chimpanzee was also administered a measured amount of milk. (Photo: D. Stiles)

I was surprised at how self-disciplined the hungry chimpanzees were. There was no fighting, and no chimpanzee tried to grab the basin or jump into the boat. When the feeding had finished, we continued down the river past the village of Marshall on the right bank, and then swung to the left up the Little Bassa River past a long sand bar, on the other side of which I could see waves crashing from the Atlantic Ocean. We passed the opening to the sea and soon we reached Island 1. John and two assistants repeated the feeding procedure.

Chimpanzees waited in the trees for the boat to arrive. The blue barrel marks the site of where fresh water is piped to the island, as the islands have no permanent water source. The river water is salty from mixture with sea water. The water pumps periodically break down, and if they aren’t repaired quickly the chimps could die an agonizing death from dehydration. (Photo: D. Stiles)

Island 1a had infants, so milk was particularly important here. (Photo: D. Stiles)

I could see that the islands would make a perfect sanctuary, if the funds could be found. One of the biggest problems with most chimpanzee sanctuaries was escape. Chimps are very intelligent and can usually find their way out of a fenced compound, if they are determined to get out. Sweetwaters in Kenya has periodic escapees, and on my visits to Tchimpounga in the Congo and Lola ya Bonobo in the DRC I learned that escapes were common – the tracking of one was in progress when I visited Lola.

Chimpanzees could not swim naturally, their huge torsos and relatively short legs made them sink like stones if they got into deep water. There would be no escapes from the islands.

Soon after returning to Kenya, Liberia was declared Ebola-free by the WHO. I met with Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) veterinary and captive wildlife officials and discussed the possibility of bringing the chimpanzees to Sweetwaters on Ol Pejeta Conservancy. I assured them that the chimpanzees were healthy and were being kept in quarantine-like facilities, away from contact with any potential virus carriers. In another meeting I met with the head of the Species Conservation & Management Division and officers in the CITES department – KWS is both CITES Management and Scientific Authorities for Kenya. They were very cooperative and helpful.

I eventually managed to obtain an official letter from KWS approving the importation of the Liberian chimpanzees and informing us that we should proceed with obtaining the necessary permits to allow the import. I sent this letter to the Liberian CITES office and requested them to issue an export permit, assuring them that Kenya would issue a CITES import permit on the basis of the letter.

In late June, Jim and Jenny Desmond arrived in Liberia from Kenya, where they were temporarily staying after completing work in Uganda. Jim is a wildlife veterinarian and Jenny is an experienced primate caregiver, both of them having worked for years in many primate sanctuaries and conducting primate health research around Africa. Jim was now the Veterinary and Technical Advisor and Jenny was Consulting Director on behalf of the Humane Society of the United States. They had come to Liberia to work with the LIBR chimpanzees and look into the possibility of establishing a sanctuary for them. HSUS was vigorously leading a huge coalition campaign to find funding, including compelling the NYBC to resume support for the chimpanzees. To date, the crowdfunding site has raised an astonishing USD 232,500.

Jim and Jenny were very helpful in assisting getting the CITES export permit issued and obtaining an official health clearance letter from the Ministry of Agriculture. Jim prepared a document certifying that he had examined the chimpanzees and they were free of disease. This was all sent to KWS and PEGAS made an official application for a CITES import permit on behalf of Ol Pejeta Conservancy. Jim and Jenny were returning on 28th July to Kenya and offered to accompany the chimpanzees on their journey, so this offered a good target date to finalize all the paperwork.

In the meantime, I found out from the Nairobi office that the Kenya Airways plane flying the Monrovia-Nairobi route, which had now resumed, had quite strict dimension requirements for cargo shipments. We would have to construct transport carriers in Liberia that could meet the required dimensions. I communicated this to Phoebe and the Desmonds and they set about organizing construction of two carriers.

KWS then informed me that we would need an import permit from the Director of Veterinary Services (DVS), under the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries, before a CITES import permit could be issued. I wrote to the DVS explaining the situation and enquired how to go about obtaining the required permit. No reply.

There is no need to go into the details of all of the efforts made to obtain the DVS import permit, but the final result was that no permit was obtained before 28th July – in spite of KWS support – and no permit has been obtained since. The problem was no doubt the fact that after Liberia was declared Ebola-free, other cases cropped up. Even though it was virtually impossible that Guey and Sweetpea could be carriers of the virus, it was simply impossible politically to allow the importation.

The chimpanzees have been moved to the LIBR facilities in Charlestown, where they are looked after by trained staff. PEGAS reimbursed Phoebe McKinney for six months of care for the chimpanzees (May to end-October) and the construction of the transport carriers. The Desmonds have returned to Liberia to carry on their extraordinary work of improving the lives of captive chimpanzees, and they report that Guey and Sweetpea are like sisters now, enjoying each other’s company every day.

If Phoebe had never reached out to PEGAS that fateful day in March 2015, the two orphan chimpanzees would still today be living a horrible existence alone, one chained to a rusting vehicle and the other staring out of bars from a bleak chamber.

Sweetpea enjoying a little reading in the afternoon sun. (Photo: J. Desmond)

Guey enjoys a banana, free of her chain. (Photo: J. Desmond)

It’s playtime for Guey and Sweetpea at LIBR (Photo: J. Desmond)

[1] See the gripping film about ‘Monkey Island’ at http://www.vice.com/video/the-lab-apes-of-liberia.